|

www.snnewswatch.com/local-news/feds-pressure-ontario-on-boreal-caribou-conservation-7164564?utm_source=SNNewsWatch&utm_campaign=2cbf7bfe52-DailySN&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_85a78531ab-2cbf7bfe52-45811288

OTTAWA — The federal government has established a timeline for Ontario to take additional steps to protect the boreal caribou and its habitat. The species was declared to be threatened since 2003. Stephen Guilbeault, minister of environment and climate change, announced last week that Ottawa is giving the province until April 2024 "to demonstrate equivalency of approach between provincial measures and the federal framework." According to Guilbeault, that timeline was previously agreed upon mutually. The minister said that after determining earlier this year that some portions of the boreal caribou's critical habitat on non-federal land in Ontario is not adequately protected, he has recommended that a critical habitat protection order be issued as required under the Species at Risk Act. Click on the link above for the rest of the article.....

0 Comments

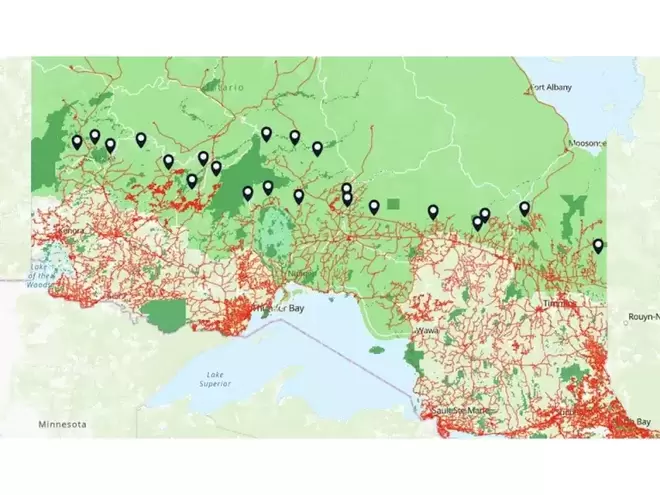

More analysis from Julee Boan, with the NRDC! his blog was coauthored with Rachel Plotkin, Boreal project manager with the David Suzuki Foundation in Canada. Whenever a conservation agreement — a recovery tool under Canada's Species at Risk Act — is announced, it is hailed as a breakthrough. Conservation agreements are intended to signal that the federal government and a partner (e.g., provincial or Indigenous government) are committed to undertaking joint actions that benefit species at risk and enhance their chances of survival. It has now been a year since Canada entered into such an agreement with Ontario for boreal caribou, on Earth Day, 2022. At the time, environmental lawyers and watchdogs expressed deep concern that the agreement would likely do more harm than good. The “caribou in the room” was that, more than a decade after the federal boreal caribou recovery strategy and accompanying guidance were published, Ontario continued to willfully ignore the fundamentals of critical caribou habitat protection, which are predicated on enforcing limits to cumulative disturbance. The conservation agreement risks the possibility of providing green cover for the province. So, have caribou’s chances of survival been enhanced under the agreement? Regrettably, the last time Ontario released any information on the condition of caribou populations was almost a decade ago. The province conducted “Integrated Range Assessment Surveys” between 2010 and 2013 to calculate caribou population size, recruitment rates, survival, population trend and probability of occupancy. The final reports were released in 2014 and survival rates showed disturbing trends of decline. Despite the lack of evidence that forest management is supporting caribou recovery, in 2020, the Government of Ontario, after years of aggressive lobbying, granted the forestry industry a permanent exemption from having to comply with the province’s Endangered Species Act – the only tool with the capacity to prioritize species recovery. It is well documented that industrial disturbance in the mature, unfragmented forests on which caribou depend is most likely driving their decline. As such, to understand how caribou are faring under the agreement in the absence of population trend data, we must turn to the province’s management of caribou habitat as the best proxy. In other words, we can look at how disturbance levels have or are likely to change under the conservation agreement in forests where logging and mining occur. According to recent research, “the 65% undisturbed critical habitat designation in Canada's boreal caribou Recovery Strategy may serve as a reasonable proxy for achieving self-sustaining populations of boreal caribou in landscapes dominated by human disturbances”, while acknowledging that some populations may be more or less vulnerable. In most ranges, the cumulative disturbance has increased; Ontario’s forest management policies continue to lead to more fragmentation of caribou habitat. (Although Ontario hasn’t publicly reported this range disturbance data since 2018.) On the ground, a number of new forestry cutblocks and roads in undisturbed caribou habitat are planned in current Forest Management Plans, as illustrated in our map below. Map of northern Ontario, Canada. (See Above) Dots show approximate location of new roads and logging planned in undisturbed caribou habitat by 2030. Remaining caribou range is shown in green and existing main roads are shown in red. Data Source: Ontario GeoHub (April 2023) and Ontario Forest Management Plans (Natural Resources Information Portal, April 2023, https://nrip.mnr.gov.on.ca/s/fmp-online?language=en_US). Ontario’s failure to take the necessary steps to recover caribou and protect existing habitat has not gone unnoticed by the federal government, which has assessed that the province is failing to effectively protect critical habitat. The assessment triggers a mandatory recommendation to Cabinet for federal intervention (called a critical habitat protection order), so we can assume that such an order is either being pulled together or has already been presented. On the heels of the federal environment minister’s assessment, Ontario committed $29 million to put toward caribou research, monitoring and protection. However, how those funds will be spent remains ambiguous. Resources are necessary to finance caribou recovery, but what Ontario has put on the table lacks a plan and targets for habitat protection and cumulative effects management. In the absence of the effective protection of critical habitat in Ontario, the federal government must stop the ongoing loss. Despite the predictable fear-mongering by forest industry lobbyists, if Cabinet issues a protection order, it lasts only five years, providing time for the province to put its funding to good use. Since Ontario has declared it could sustainably double the amount of logging in the province, industry’s bemoaning that protecting more caribou habitat will “devastate” northern economies has been met with considerable skepticism. Federally, the government has committed to halt and reverse nature loss, an essential measure to forestall an imminent sixth extinction crisis. It has the authority under the Species at Risk Act to intervene, and a recent Commissioner on the Environment and Sustainable Development report has critiqued the ministry’s failure to issue these orders. Further, despite the growing use of conservation agreements to advance caribou protection across Canada (eleven conservation agreements have been signed for boreal and southern mountain caribou since 2019), none of these agreements have met the important criteria to protect critical habitat in alignment with the Species at Risk Act. A pause on new roads and logging in undisturbed areas until critical caribou habitat is effectively protected, while third-party monitoring is conducted to update our understanding of the condition of caribou populations, could slow declines and provide the needed pivot toward recovery. It’s time for the Ontario government to share how the $29 million will be spent to protect caribou habitat and monitor populations and for Canada to show leadership by implementing a protection order. April 22nd EARTH DAY Action Request

To: FOW members and supporters Fr: FOW Conservation Committee Re: Contact: Federal Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault Copy to: Ontario Environment Minister David Piccini Suggested Message: Dear Minister Guilbeault, I am writing to request that you issue a federal protection order for a 5 year moratorium on new woodland caribou habitat degradation/roads on forests like Ontario’s Wabadowgang Noopming WHILE the province of Ontario conducts population surveys with their recently announced $29 million in funding. (Include any key points as per our backgrounder below) Steven.Guilbeault@parl.gc.ca Or mail to: House of Commons, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada K1A 0A6 Please send a copy to: David Piccini, david.Piccini@pc.ola.org; Or mail to: Ministry of Environment, Conservation and Parks, 5th Floor, 777 Bay St., Toronto, Ontario M5B 2H7 Please consider a Letter to the Editor of your local newspaper. --------------------------------------------------------------------- FOW CONSERVATION UPDATE – April 2023 Friends of Wabakimi are deeply concerned about the continued loss of essential habitat for woodland caribou and associated wildlife species. Boreal caribou are listed as a threatened species under Canada’s Endangered Species Act as well as by Ontario and other provinces. Ontario defines threatened as “….likely to become endangered if steps are not taken to address factors threatening it.” The recently adopted 10-year forest plan for the Wabadowgang Noopming forest continues new roads, clearcutting and habitat destruction immediately adjacent to Wabakimi Provincial Park and other surrounding parks & conservation reserves. Two MNRF maps show the areas planned for road building and clearcuts in the near term. (Map 1, Map 2) FOW actively participated in this forest planning process. The FOW supports challenges to this forest plan as unsustainable for wildlife, habitat and recreational values. The loss of boreal forest habitat is concerning others as well. Here’s a summary of what we know. Canada’s Federal environment minister Steven Guilbeault has told Ontario they are not effectively protecting the habitat of boreal caribou. Currently Mr. Guilbeault is pressuring Quebec to protect caribou. An Environment Canada five-year federal protective order is one possibility which raises the issue to high prominence; but the practical effect is unclear. (The minister recommends and the federal cabinet decides…a process that’s not public.) This is after Ontario signed a Boreal Caribou agreement with the federal government with lofty goals of collaboration, monitoring and protection. Immediately, this was criticized by the Wildland League (CPAWS chapter), as lacking actual habitat protections. On March 15, 2022, Ontario’s minister of environment, conservation and parks David Piccini pledged $29 million over four years to support habitat restoration and protection and research. Lakehead University in Thunder Bay is slated to receive significant funding. Which department will receive the funds and how will this be spent? While monitoring of woodland caribou populations is clearly needed; will it make any difference if habitat loss continues? FOW is reaching out to Lakehead to learn more. Julee Boan, now with the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDE), and previously with Ontario Nature addressed these issues recently and noted Ontario’s weakened Endangered Species Act and the intense push-back from the timber industry. Our understanding now is that the federal government is still looking for ways to work with Ontario in some sort of cooperative sense. FOW’s (and others’) position is that there should be a moratorium on new caribou habitat degradation/roads (through the protection order for 5 years) WHILE the province conducts population and habitat surveys with their $29 million in funding. Ontario Nature Protected Places campaign. FOW has previously proposed areas near Wabakimi Provincial Park further protection, i.e. conservation reserves. These are now indicated on Ontario Nature’s story map. Protection and Preserving the Boreal Forest The bigger issue is the boreal forest and ongoing threats. As noted by Environment America, the boreal forest is the Amazon of the North, essential for global climate health. Trees that have grown for decades in the boreal forest (the largest intact forest on Earth, stretching from Newfoundland to Alaska) are chopped down to make tissue products that are used for mere seconds. Canada is one of 105 signatories to The Glasgow Declaration on Forests, announced in 2021 at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference (COP 26). It calls for halting and reversing forest loss and land degradation by 2030, and that achieving our global climate targets requires protecting and restoring forests. The European Union (EU) issued a new regulation last December to not allow products coming from areas of deforestation as well as “degradation.” The EU is a consumer of wood pellets from Ontario and Canadian forests. Natural Resources Canada (NRCAN) has given the industry’s FPAC $750,000 of public money to promote that Canadian forests are not degraded. (NRCAN is the federal ministry that promotes Canadian forest products. NRCAN lobbied against the EU regulation.) FOW supports petitioning the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers, (a consortium of federal and provincial officials), for a clearer definition of “forest degradation,” which should state, “Forest degradation is evidenced by widespread decline in bird habitats and populations, significant habitat fragmentation and shifts in age structure in forests managed for timber extraction, and the fact that only 15 of Canada’s 51 boreal caribou herds have sufficient habitat remaining to survive long-term.” Environmental and NGO organizations advocating for woodland (boreal) caribou and their habitats include: David Suzuki Foundation (https://davidsuzuki.org/action/protect-canadas-forests-from-degradation/) Ontario Nature (protected places) Environment North (based in Thunder Bay, ON) Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) The Narwhal (independent environmental journalists) PEW Memorial Trust World Wildlife Fund Canada Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society Canada Geographic Alberta Wilderness Association As if these challenges are enough, the province of Ontario is encouraging a mining boom in the boreal forest. Several large projects are proposed in areas both immediate east and west of Wabakimi Provincial Park. Research is needed to understand the environmental risks and economic alternatives. MNRF Plan for Wabadowgang Noopming Forest (W.N.) provides Bleak Prospects for Woodland Caribou1/30/2023 Summary of Public Comments - NEW (Paddlers! Have you seen woodland caribou or signs, in SE Wabakimi P.P., Tamarack Lake, Lookout River & Boiling Sands Rive;, Crown land routes- Collins, Fawn, Doe, Tunnel Lake, Rushbay, Vale Creek, D’Alton, Caribou and Little Caribou, Linklater, Raymond River, Big Lake, Big River, Pawshowconks etc. We have do citizen monitoring! We need photographs, video and anecdotal evidence of caribou in these areas. Please let us know! Send to info@wabakimi.org) The Friends of Wabakimi participated in this 10 year forest planning process administered by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) as detailed on our Conservation Page. The Wabadowgang Noopming Forest (W.N.) is immediately adjacent to Wabakimi Provincial Park; just north and SE of Armstrong, Ontario. It was split off the larger Nipigon Forest and has operated under a two-year contingency plan since. MNRF has now issued their near final determinations. (See their determination here) This is after FOW participated in the Dec. 6th in-person Issues Resolution Meeting with MNRF staff and many other interested parties. (Update: Logging/road map 1; Logging Road Map 2) We achieved some modest goals: 1) A primary logging road was rerouted to lessen the long-term impact on the D’Alton Lake area, currently subject to ongoing harvest. 2) Small increases in buffers around known canoe routes. 3) Made known to MNRF and all parties that there’s a growing constituency that supports canoe routes and essential habitat protection. But the overall end result promotes forest harvest activities and road building into virgin forest with little regard for the long-term impacts on woodland caribou. One distressing feature of the MNRF’s decision is the lack of any established monitoring. Referring to the area SE of Tamarack Lake, the decision says, “As there is no known and verified caribou values present in this area at this time there is no area of concern prescription applied for caribou in this location of the forest.” How would they know? No monitoring has been done in recent history. Essentially, MNRF is flying blind when it comes to the long-term impact on essential woodland caribou habitat. They’ve made it clear it may be up to us to provide knowledge of caribou presence. The FOW Board reviewed these issues at their last meeting and determined, after some strenuous discussion, to support Bruce Hyer and other advocates in efforts to question and potentially challenge this plan insofar as the plan is not sustainable for caribou, park values, ecological values, general recreation, and remote tourism. That could entail being a “Friend of the Court” for an injunction proceeding or filing a petition under the Federal Endangered Species Act. Regardless, FOW has strived to build good relations with local communities, First Nations, and land managers such as the MNRF. We will continue to do that in the hope that better understandings and collaborative solutions are possible. What else can we do now or in the future??

Fr: Vern Fish, Friends of Wabakimi - President,

Dave McTeague, Friends of Wabakimi - Board Chair Maurice Poulin, Board of Directors To: Mitch Legros, Ministry of Natural Resources & Forest Jeff Cameron, Wabadowgang Noopming Forest Plan Author Re: Request for Issue Resolution Date: November 6, 2022 Dear Sirs: As you will recall, we have been long concerned about, and commented upon, proposed roads and logging in and near three areas adjacent to Wabakimi Provincial Park and inside the special land use zone of CLUPA 2616.

The Crown Forest Sustainability Act directs the Minister to not approve plans which cannot be shown to be sustainable for all forest values. We believe that our suggestions above will result in an FMP that is more sustainable than the proposed draft plan. What are the next steps? What other information do you require? Respectfully, Vern Fish Dave McTeague Maurice Poulin President Board Chair Board Member To: Jeffrey Cameron RPF, Date: July 31, 2022

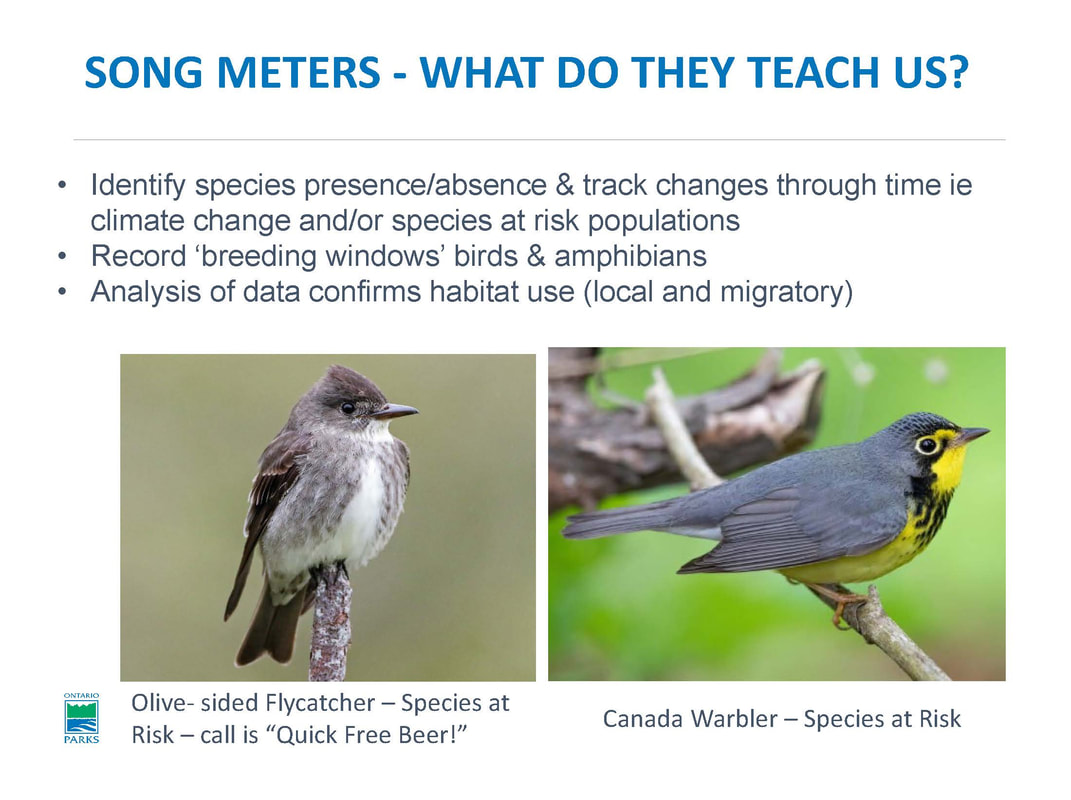

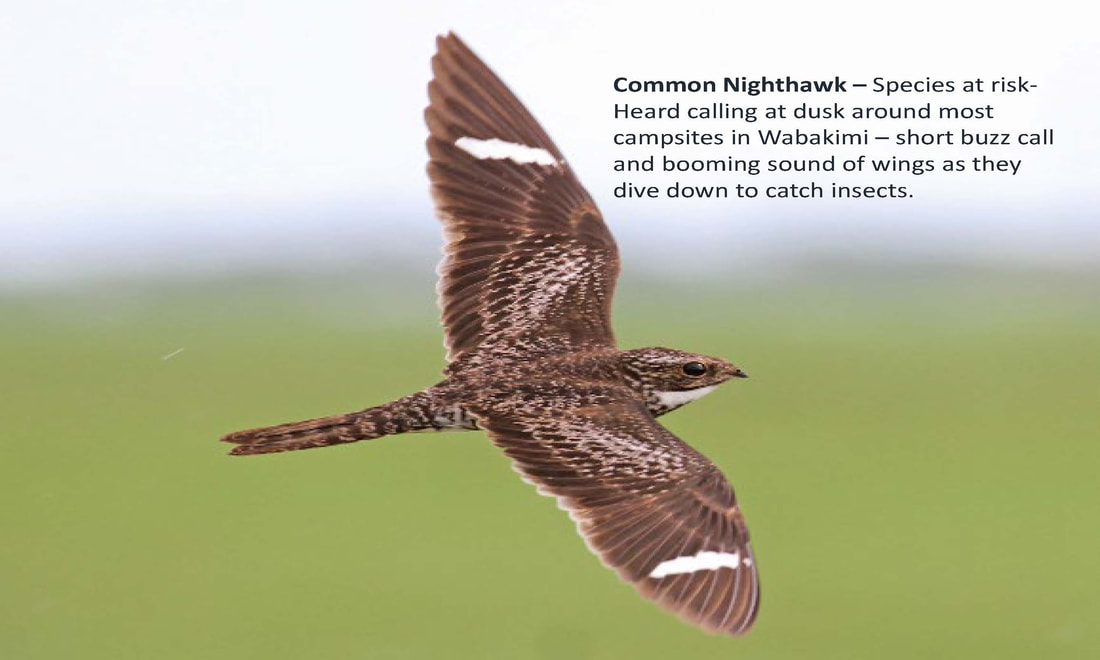

WN Forest Plan Author Fr: Vern Fish, President Friends of Wabakimi Re: Stage Four Comments Wabadowgang Noopming Forest (WNF) 2023-2033 Management Plan Dear Mr. Cameron, As you know, I represent the Friends of Wabakimi (FOW) on the Wabadowgang Noopming Forest LCC. The Friends of Wabakimi is a non-profit organization registered in the Province of Ontario. Our mission is to “advocate for the protection and preservation of the diverse natural, cultural and historical resources of the Wabakimi Area”. The FOW define the Wabakimi Area as a 2,572,734 hectare virtually roadless tract that includes Wabakimi Provincial Park and a host of surrounding provincial parks, Conservation Reserves and Crown land. The Wabadowgang Noopming Forest (WNF) is part of the Wabakimi Area. A Sense of Wilderness I attempt to keep the Board of Directors up to speed on the progress of the forest management plan for the WNF. They feel that maintaining a sense of wilderness in the WNF is an important value to be preserved. FOW’s priorities and concerns fall under the following topics: 1) Ecological integrity and sustainability 2) Protect critical habitat for species at risk 3) Maintaining a healthy and sustainable woodland caribou population 4) Protect exceptional recreation and tourism values adjacent to Wabakimi Park: *Maintain existing and potential wilderness tourism business opportunities *Preserve historical canoe routes that directly or indirectly connect to adjacent provincial parks *Allow limited access to historical canoe routes across the WNF Crown Land Use Policy Atlas (CLUPA)* The policies of CLUPA 2616 covers the WNF north of the Big River. “Road access will be managed to maintain commercial tourism and fish and wildlife habitat. Operating and annual plans will contain specific guidelines for the protection of tourism values and fish and wildlife habitat.” We understand that forest management and logging are allowed in CLUPA 2616. We appreciate the effort that has gone into using the McKinley Road to access Block AB-3 to avoid building a road between Caribou Lake and D’Alton Lake. We note the effort to prevent road access to the Michell Lake and creation of buffers to insulate historic canoe routes. We also note the effort to decommission secondary roads once they are abandoned. We also note that even though the Big Lake Road is signed "Road closed to unauthorized vehicles. Access prohibited under PLA. This gate is currently open, and the intent is to keep it open.” (Page 179). We assume this means that recreational paddlers can still use the Big Lake Road to access the Big Lake and the Big River. As noted, the FOW encourage limited access to historical canoe routes. *Please note that on page 73 of the Management Plan it appears that CLUPA 2616 has been mislabeled as CLUPA 2619. Species at Risk CLUPA 2616 does focus attention on maintaining fish and wildlife habitat. Page 198 of the draft forest management plan notes that “known nests will not be destroyed”. Page 47 provides a list of birds identified as Species at Risk. This list includes: Canada Warbler, Olive Sided Flycatcher, Common Nighthawk and the Bald Eagle. All of these bird species and many more have been identified along Big River canoe route which includes the Reef Lake Peninsula. Evidence of caribou was also found along the Big River. The attached memo, Reef Lake Peninsula Harvest Area, provides details and supporting documentation. As a result of this documentation, the following motion was approved by the Board of Directors of the Friends of Wabakimi at their June 26, 2022 meeting. “To maintain the habitat and the wilderness values of this potential conservation reserve, the Friends of Wabakimi strongly recommend that the Reef Lake Peninsula NOT be considered for logging.” Herbicides & Rocky Road In the Summary of the Wabadowgang Noopming 2033-2033 Forest Management Plan on page 10, herbicide use was identified as a major issue. At this time it is unclear as to whether herbicide use would be acceptable to all stakeholders particularly in the areas that the Rocky Road would make accessible. If herbicides are not acceptable and cannot be used as silviculture strategy to regenerate the forest after the cut, will this block still be logged? If not, will the Rocky Road still be needed? Wabadowgang Noopming Draft Forest Management Plan 2023-2033 Forest Management Plan Timetable www.wabakimi.org; info@wabakimi.org

March 21, 2022 To: Public Input Coordinator, Species at Risk Branch, Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks; 435 James St South, Thunder Bay, ON P7E 6T1 Canada borealcaribouconservation@ontario.ca Strategic Priorities Directorate; Canadian Wildlife Service; Environment and Climate Change, Canada 15th Floor, Place Vincent Massey Gatineau, QC K1A 0H3 ec.eccc-caribou.ec@canada.ca From: Friends of Wabakimi, Vern Fish-President Re: Proposed Conservation Agreement for Boreal Caribou in Ontario. The Friends of Wabakimi is an Ontario Non-profit corporation based in Thunder Bay, Ontario with over 260 members. We advocate for canoe routes and habitat protection in the Greater Wabakimi area which includes numerous provincial parks, conservation reserves and five managed forests. Our Mission Statement: Through volunteer stewardship and collaboration with other stakeholders, the Friends of Wabakimi will participate in the planning processes to advocate for protection and preservation of the diverse natural, cultural, recreational and historical resources of the Wabakimi Area. Friends of Wabakimi appreciate the opportunity to comment on the Conservation Agreement for Boreal Caribou in Ontario. https://ero.ontario.ca/notice/019-4995 Friends of Wabakimi and our precursor organization, The Wabakimi Project, have paddled and mapped canoe routes in this large area. We’ve seen the beauty of the boreal forest up close, and the occasional caribou as well. While this proposed agreements states many important goals and plans; we’re not clear on the implementation steps to accomplish them. Our concern is that another agreement serves to “check off the box” with little actual progress to protect boreal woodland caribou as a keystone species; an indicator of the overall health of the ecosystem and the boreal forest. We would be interested to know what concrete action steps have been taken in the Alberta/Canada agreement to date? Currently, we’re deeply involved in the planning process for the Wabadowgang Noopming Forest 10-year plan. This prime caribou habitat is bordered on three sides by Wabakimi and Whitesands Provincial Parks. The planned timber harvest is certain to continue the fragmentation of this key forest. Our forest plan comments (found here) support efforts to minimize the impact of forest harvest and promote restoration of the harvested units. What’s not at all certain though, is that once the boreal caribou leave the disturbed areas, will they ever actually return? Enhanced monitoring might answer that question, but by then it could be too late. Friends of Wabakimi have proposed three areas for new Conservation Reserves in the Wabadowgang Noopming Forest, areas which are known for woodland caribou habitat. Further, Friends of Wabakimi has proposed new Conservation Reserve for the Misehkow Valley area, which is NW of Wabakimi Provincial Park, south the Albany River Provincial Park and bordered on the west by the Caribou Forest. And we’ve proposed the modest addition of Survey Creek adjacent to the Obonga-Ottertooth Provincial Park. These modest areas of proposed protections would be an important, but by no means adequate, for the future of boreal woodland caribou. We urge both the respective Ontario and Canada ministries to consider our proposals and similar proposals, which would protect the forest from the fragmentation that threatens boreal woodland caribou. However, the forest planners and Ontario’s MNRF say that new Conservation Reserves are beyond their mandate and scope. But clearly, this is within the scope of the Species at Risk Branch of the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks. Serious consideration of these proposed Conservation Reserves should be included in the implementation plans for this Ontario/Canada agreement. In regards the proposed Ontario/Canada agreement:

The Friends of Wabakimi (FOW) has proposed four new Conservation Reserves and limitations on planned logging roads with our formal comments for the Wabadowgang Noopming (W.N.) Forest ten year plan (2023 to 2033). These four areas are closely proximate to Wabakimi Provincial Park and within the woodland caribou special area of concern. The FOW also clarified that Trail Lake (aka Tamarack Lake) Road should remain undeveloped so as to not cause increased pressure onsensitive caribou areas in Wabakimi Provincial Park’s SE corner.

The FOW represents wilderness paddlers and recreational businesses with a current membership of over 250 who have an interest in the Greater Wabakimi Area. The FOW is the successor organization to The Wabakimi Project, which explored and mapped routes, portages and campsites over a fourteen year period. The maps for the W.N. Forest are contained in Wabakimi Canoe Routes Volume 5. FOW President Vern Fish is our representative on the W.P. Forest Local Citizens Committee (LCC). Previously, FOW met with the MNRF and their consultants. Of significance is Ontario’s Crown Land Use Policy Atlas Policy (CLUPA) Report G2616: Caribou Lake / Wabakimi, adopted in 2006, which states, “The primary use for this area will be commercial tourism. Extractive activities such as timber harvesting, while growing in importance, will remain secondary. Road access will be managed to maintain commercial tourism and fish and wildlife habitat. Land use conflicts will be resolved recognizing the importance of commercial recreation in the area.” Proposed Conservation Reserves While creation of new Conservation Reserves is outside the purview of the Ministry of Natural Resources Forestry’s (MNRF) forest planning process; it is within the broad responsibilities of the MNRF generally.

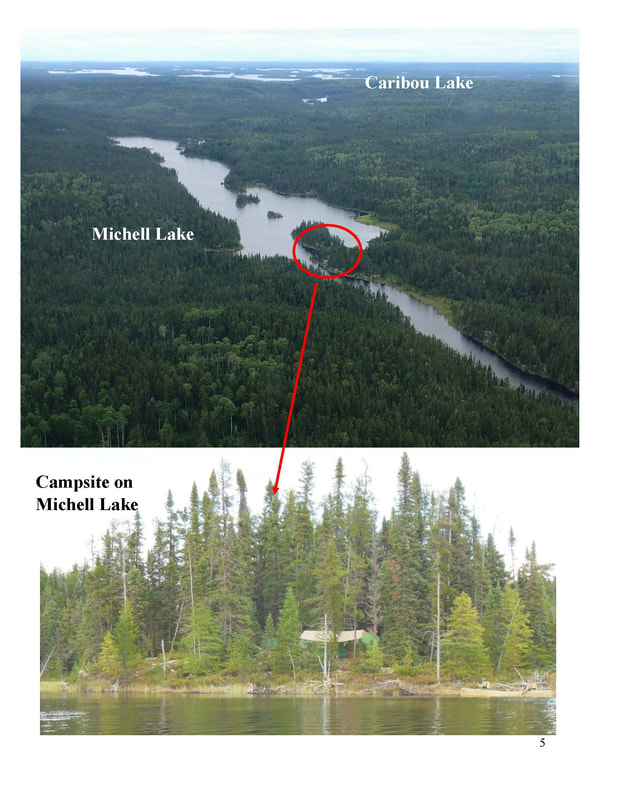

The D’Alton Block has an unusual high concentration of interconnected small lakes and rivers. It has been documented as historical caribou habitat and migration corridors. There are several valuable remote tourism outposts scattered across the “block”. This tangle of lakes has the potential to be enhanced for recreational canoeing and creates opportunities for canoe outfitting for the Whitesands community. Currently, canoeing access to the D’Alton Block is limited to portaging in from Caribou Lake. If the existing Big Lake Road were opened to recreational use up to the stream crossing just south of Big Lake, another route would be available to paddlers. This limited access would still maintain the wilderness character of the outpost cabins. It would also help reduce canoeing pressure on caribou calving on Caribou Lake in May and June. 4. Doe-Fawn Lake Complex – This area is located north and northeast of Collins. It is bounded on the south by the CNR Line, on the west and north by Wabakimi Park and on the east by Fawn and Doe Lakes. This area features shallow soils and is important currently used year-round caribou habitat. This small but important area deserves status as a Conservation Reserve to protect this caribou habitat. Eliminating or limiting road access and designating the area west of Doe and Fawn Lakes as a Conservation Reserve will accomplish both of these goals. Roads inside of CLUPA G2616. We are recommending some areas within CLUPA G2616 for Conservation Reserve status. That designation lies outside of the scope of the forest management planning process (FMP). However, it does lie within the responsibilities of Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF), and this is a Crown FMU. The Crown Forest Sustainability Act (CFSA) makes it clear that the Minister shall not sign any FMP that is not sustainable for all forest values. So, this draft FMP can, and should:

Of particular importance for lowest possible grade, temporary (perhaps winter) roads are:

These roads should be winter roads… or left just in the current state to keep open the possibility of increased formal protection of the caribou habitat and remote recreational experience. A Sense of Wilderness According to Vern Fish, FOW President, “Our goal is to maintain a sense of wilderness in key parts of this forest… Wabakimi has important values to be preserved. Our FOW priorities and concerns are: -- Ecological integrity and sustainability -- Maintaining a healthy and sustainable woodland caribou population -- Protect lakes that support Lake Trout -- Protect exceptional recreation and tourism values adjacent to Wabakimi Park: *Maintain existing and potential wilderness tourism business opportunities *Preserve historical canoe routes that directly or indirectly connect to adjacent provincial parks.” “We do understand the need for economic benefit to Whitesand First Nation, and Armstrong. We believe that the - above recommendations are consistent with long term sustainability for both the natural environment and local economy.” Contact: Vern Fish, FOW President at info@wabakimi.org FOW Mission

The FOW will participate in the planning process to advocate for the protection and preservation of the diverse natural, cultural and historical resources of the Wabakimi Area. Background Vern Fish and Shawn Bell represent the FOW on the Local Citizens Committee (LCC) that provides input to the forest management planning process for Wabadowgang Noopming Forest Management Plan. This is the Crown Land that separates the Wabakimi Provincial Park from the Community of Armstrong, Ontario. This area is over a million acres and it includes the Raymond River, Big River and Collins River canoe routes. As part of the forest management process a Contingency Plan (CP), a two year plan, is written to provide direction for forest management activities until the ten year plan can be completed in 2023. The FOW submitted comments to Contingency Plan - Stage Three Review of Proposed Operations on November 22, 2020. See previous Conservation post. The CP is followed by a more intensive discussion to result in a 10 year forest plan. The Plan Author, Jeffery Cameron of NorthWinds Environmental Services, provided a detailed response to our comments and offered to set up a virtual meeting with representatives of the Ministry of Natural Resources & Forestry and members of the writing team to answer our questions. This meeting was conducted on January 25, 2021. The following FOW board members participated in this call: Dave McTeague, Randy Trudeau, Ian Curran, Victoria Steeves, Ray Tallent and Vern Fish. MNRF staff included Robin Kuzyk and Steve Young. Meeting Summary The following topics were discussed: 1) Caribou Management Caribou are an endangered species in Ontario. Their management is guided by the Dynamic Caribou Habitat Schedule (DCHS). For more details on DCHS go to (https://files.ontario.ca/environment-and-energy/species-at-risk/277783.pdf) The CP provides for logging operations in the Dalton Block which is an area between Caribou Lake and the D’Alton Lake. This area is recognized as a calving area for caribou and is also noted for remote tourism values. The Big River canoe route flows through this region. (See Volume 5 of the FOW canoe route booklets). The logging is designed to create more caribou habitat but could have a short term impact on caribou and recreational Areas of Concern (AOC). The FOW have pointed their concern for both impacts. The staff pointed out that these concerns have been taken into account by creating AOC’s which require buffers for the logging operations. The logging will also only be done during the winter months to further reduce the impacts. 2) Placement of Primary Roads The logging road leading up the Dalton Block is currently scheduled for winter access only and is defined as a secondary road. It has been proposed that this road be upgraded to a primary road which would make it permanent and allow summer use. This decision will be finalized in the Forest Management Plan which is scheduled to be completed in 2023. The FOW noted their concern about the impacts of a permanent road. 3) Crown Land Use Policy Atlas Policy, Report G2616: Caribou Lake / Wabakimi This policy states that the area around the Dalton Block should be managed primarily for recreational and wildlife purposes. The staff pointed out that this policy does not prevent logging and is only one policy impacting the forest management plan for this area. 4) Road Access for Recreational Canoers The FOW does not want to break up the wilderness with roads. However, if a road is going to be built for other purposes can this road also be used for canoeing access? The Big Lake Road provides access to the Dalton Block. We would like to see access to the Big River canoe route off of the Big Lake Road if possible. Road access to Crown Land is covered by other aspects of Ontario law. Thus, this becomes a complicated administrative question for the MNRF to answer. We did not get a definite answer to this question at this time. 5) Canoe Route Maintenance We asked if we could explore the possibility of working with the MNRF to help maintain canoe routes within the Wabadowgang Noopming Forest. These routes include the Raymond, Big River, Collins River and parts of other routes. The staff recommended that we talk to Emily Hawkins, Resource Operations Supervisor, about work permits and other details. 6) Process for creating consensus on primary roads A big controversy brewing in the LCC has been the placement of primary roads to provide access to logging units near the border with Wabakimi Provincial Park. The FOW has recommended that a facilitator be used to build a consensus on this issue. This issue will be discussed further at a future LCC meeting. (for a really deep dive into these forest management issues here's a recent summary!) |

AuthorJoin the Conversation and be part of Process Archives

March 2024

Categories |

©2020 Friends of Wabakimi All Rights Reserved